Book & Film Review

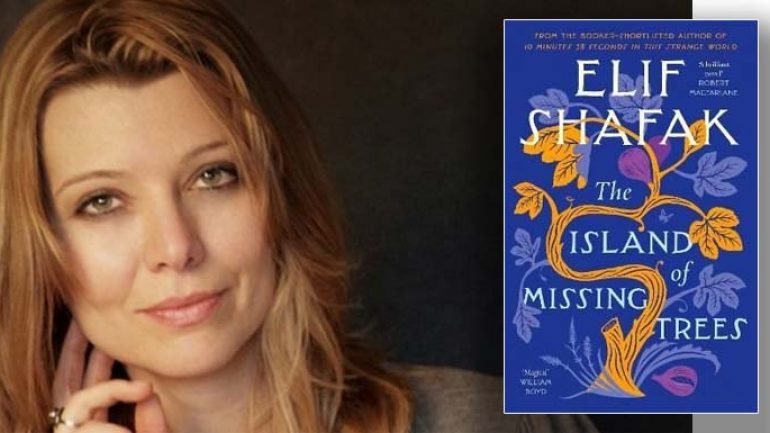

The Island of Missing Trees – Elif Şafak

Elif Şafak is a controversial name in Turkey, both because of what she writes and what she says. The fact she chooses characters from minority peoples and religions in Turkey in her books, and brings these characters face to face with characters suitable for the “Muslim Turkish family structure”, causes her books to make a sound. In 2017, the criticism of her “trying to attract attention” increased when she announced she was bisexual.

There is one thing I agree with, Şafak carries out her PR work well and manages to mention her name every time. So much so that I can’t stop my urge to poke around at her latest book, even though she’s not an author I enjoy reading.

It was like that again, and with the translation of the book that Şafak published in English in 2021 into Turkish, I got the book and read it. Since it is the author’s first attempt at a book in English, of course, it would be better to see how she wrote in that language, but I guess I was a little lazy about that.

The book is based on a conflict readers have encountered in her other books: the touching story of young lovers Kostas and Defne, one Greek and Christian, the other Turkish and Muslim.

The situation of a divided country after the Cyprus War is conveyed through two lovers who fell apart. This is a distinctive feature of Şafak’s novels. Physical and social conflicts within a country are told through the relationships of ordinary young people who will represent the parties. This is a sensible way to show the destructiveness of conflicts in ordinary lives, and Dawn uses it successfully.

The novel moves back and forth in time and space. The love affair between Kostas and Defne, who is an islander, started in 1974, before the “Cyprus Operation”, constitutes the first time. 2010 is the last period in London; They are married and have a daughter.

The fig tree, the witness of the love of two young people, tells a large part of the novel. This fig tree, which was uprooted from one side of the island, moved to another place, to the British border and replanted, becomes the narrator of the history of Cyprus and human stories. It is used for a functional purpose, beyond being a successful metaphor.

In 2010, we meet 16-year-old Ada (the Turkish word meaning island, also used as a girl’s name and represents Cyprus Island), the daughter of Kostas and Defne. The island does not know or recognize either Cyprus or the Turkish and Greek families in Cyprus. However, at the point where the dramatic elements of the events rise, Ada learns something.

The novel illustrates well how social traumas affect our present, our ‘new lives’ and our relationships with our children. It tells how moments of happiness are lost because of the anxiety of losing it.

Readers encounter some cliché analogies and repetitive narratives. However, the effect of the impressive ending remains in your memory.

Ivy – Tolga Karaçelik

Tolga Karaçelik is one of the late Turkish directors. He is a director who manages to deal with common subjects in an original language.

Karaçelik’s second feature, Ivy (2015), carries the feeling of being stuck on a huge cargo ship. We watch the six-man crew on this freighter come to terms with themselves and each other.

Departing from the port of Istanbul, the ship named Ivy anchors in international waters by maritime law due to the shipowner’s declaration of bankruptcy during the voyage. The ship will crash offshore until a buyer is found—probably for an indefinite period. The freed crew leaves the ship.

At first, things seem easy for the captain and the five sailors: Since they are not cruising, they will only deal with routine work, and while they wait for the ship to be sold, they will earn money “from the place they lie down”. But over time, food and supplies begin to run out, the uncertainty of the situation drags on, and the nerves become strained.

The location is a ship that gradually turns into a prison. Men with weakened connections with the outside world constantly tell each other stories. The movie begins with the call of the ship’s captain, “We must be united, we must act together”. But tensions escalate between the crew, who are left alone, and things get out of hand, step by step.

In this respect, the ship in the film is a social structure; becomes a metaphor for family or country. The family and the state constantly remind their members of the importance of unity and togetherness; This is the general condition of staying in control. However, conflicts of interest, competition and personal ambitions will hinder the merger and damage the structure.

In order for the ship to be read as a country metaphor, the director also placed explicit elements in the film. The characters are chosen as religious, Kurdish, conservative and rebellious; They are all different from each other, but their destinies are intertwined. What happens to the ship will affect the lives of all of them.

Fighting with power is undoubtedly a brand new issue, neither in the history of cinema nor in the history of literature. However, the movie Ivy manages to stand out among other examples. Because the director manages to reflect the tension quite well. Moreover, while doing this, he continues to maintain subtle sarcasm.

In the final part of the movie, a semi-fantastic layer is added on top of the increasingly frustrating relationships. A state of collective paranoia envelops the entire ship like ivy. Accompanied by dark shadows, unseen voices, fear and regret, everyone is on the verge of going crazy.

The opening sequence, which makes it feel like the crew came together in response to an almost mysterious call, gains a different meaning with this fantastic touch. Nightmares, hallucinations, and claustrophobia give the film the feel of a ghost story, while Ivy is at full throttle towards a finale that is open to different interpretations.